Incentivizing Endowed Chairs at Public Universities: A U.S. 50-State Policy Analysis

Legislative Instruments for Endowed Chair Incentives

State legislatures have deployed a range of legal instruments to spur the creation of endowed faculty positions at public universities. Key legislative approaches include:

State Matching Fund Laws: Many states have enacted laws establishing matching grant programs that provide public funds to match private donations for endowments. These programs, implemented in at least 24 states by the early 2000s, typically authorize the state to contribute a certain amount (e.g. dollar-for-dollar or one dollar per two dollars donated) to university endowment funds when private gifts are secured. For example, Massachusetts’ Public Higher Education Endowment Incentive Program (originally 1996) mandates a state match of $1 for every $2 in private contributions for academic endowments. Florida created a Trust Fund for Major Gifts in 1985 to match private gifts for endowed chairs and other purposes. Texas launched the Texas Research Incentive Program (TRIP) in 2009, offering tiered state matches (50%, 75%, or 100% depending on gift size) for donations to research endowments. These matching fund statutes formalize public-private partnerships by leveraging state dollars to “double” or otherwise augment private endowment gifts.

Tax Incentives for Donors: A few states use tax policy to encourage donations to public university endowments. This approach is less common than direct matching funds but can include state income tax credits or deductions for charitable contributions targeting higher education endowments. For instance, Arkansas offers a tax credit (33% of the donation amount) for gifts to approved research endowments or research park authorities. Some states provide modest credits for any donations to public college foundations (e.g. a $50 individual tax credit in Arkansas for contributions to colleges). While federal tax deductions already incentivize charitable giving, these state-level credits aim to amplify the incentive for individuals and corporations to endow professorships. Legislatures have to balance such credits with fiscal impacts on state revenue, so tax incentives are typically capped or limited in scope.

Public-Private Partnership Frameworks: Several states have embedded endowed chair initiatives within broader industry–university partnership programs. In these cases, legislation promotes collaboration between public universities and the private sector by linking faculty endowments to economic development goals. For example, Georgia supports endowed “Eminent Scholar” chairs through the Georgia Research Alliance, a state-funded non-profit initiative that requires at least a 1:1 match from private industry or foundation partners. South Carolina’s Centers of Economic Excellence Act (2002) created an endowed chairs program (the “SmartState” program) funded by state lottery revenues, which awards matching funds for endowed professorships in key research areas chosen in partnership with industry. These legal frameworks often establish oversight boards (including industry representatives) to review proposals for endowed chairs that align with state economic priorities. By statute, companies that sponsor a chair or contribute to these programs may gain preferential collaboration opportunities – for example, a role on advisory boards of research centers or first access to partner on state-funded R&D projects – though explicit procurement preferences are generally avoided. The emphasis is on mutual benefit: universities get endowed posts to attract top talent, while industry gains access to expert researchers and innovation ecosystems fostered by those faculty.

In summary, state legislatures have crafted a toolkit of laws – matching fund programs, tax incentives, and partnership mechanisms – to catalyze the growth of endowed chairs and professorships. These instruments create a policy environment in which private donors are encouraged (and even financially rewarded) to invest in public higher education, thereby multiplying the impact of public funds and strengthening university faculties.

Incentive Mechanisms and How They Work

Legislative measures employ several incentive mechanisms to encourage the establishment of endowed faculty positions:

Matching Fund Schemes: The cornerstone of most state programs is a matching funds scheme where public money matches private donations at a set ratio. Many states opt for dollar-for-dollar matching (1:1) – for example, Kentucky’s “Bucks for Brains” endowment trust fund matches each private dollar with one state dollar. Others use a partial match; Massachusetts and Connecticut set a 1:2 match ($1 state for every $2 private). Some programs have tiered matching ratesto incentivize larger gifts: Florida historically matched 50% for mid-sized gifts, escalating to 100% match for the largest gifts (over $2 million). Similarly, Texas’s TRIP provides a 50% state match for gifts $100k–$1M, 75% for $1M–$2M, and 100% for gifts above $2M (up to $10M). These schemes effectively leverage private capital, stretching donors’ contributions further. For instance, Massachusetts’s initial program in 1997–2003 saw the state’s $50 million in matches spur over $125 million in private donations – a 250% return on public investment. Matching funds may be appropriated annually or set up as a trust/endowment whose earnings fund the matches (as in Kansas, where the state provides an “interest equivalent” match on endowed gifts). The promise of state matching is a powerful incentive: it signals to donors that their gift’s impact will be multiplied, often prompting larger donations or accelerating the timeline of giving.

Preferential Access and Partnership Benefits: While less formalized in statutes, some incentive programs confer indirect benefits to donors, especially corporate donors, in the form of partnership privileges. For example, states focusing on industry-linked endowed chairs (such as South Carolina’s SmartState program) invite contributing companies to help shape research agendas and collaborate with the endowed professors. Under the SmartState law, one-quarter of the award funds are aligned with requests from the state’s Secretary of Commerce to ensure relevance to industry needs. In practice, a company that contributes to an endowed chair in, say, automotive engineering might gain access to state-supported research centers, opportunities to beta-test technologies developed by the professor, or networking advantages in state economic development circles. Some states have considered more explicit incentives, such as expedited licensing of university-developed intellectual property for companies that endow faculty positions, or giving donors priority in state innovation grant programs. While direct procurement preferences (e.g. favorable treatment in unrelated state contracts) are typically not codified due to ethical concerns, the collaborative frameworks often serve as a quid pro quo: donors become key partners in university research enterprises, frequently earning seats on advisory boards or task forces that guide state R&D initiatives. These measures create an incentive beyond the financial match – donors gain influence and insider access to cutting-edge projects and talent.

Public Recognition and Honorary Rewards: Donors who endow professorships are often incentivized by recognition mechanisms built into the program. Most universities, enabled by state policies or board regulations, offer naming rights for substantial endowed gifts – the donor’s name (or a honoree’s name) is attached to the endowed chair or professorship. State matching programs typically work through university foundations, which can honor donor intent with such naming; some state laws explicitly mention that matching funds apply to “endowed chairs, professorships, scholarships, and other academic purposes”, thereby endorsing these naming opportunities as legitimate academic purposes. Additionally, states sometimes create honorary titles or awards for major patrons of public higher education. For instance, Texas has publicly celebrated donors whose gifts qualified for TRIP matches, and Florida in the past conferred the “Eminent Scholar” designation to chairs funded by donors and state match, which brings prestige to the donor as well. Some legislative frameworks encourage universities to include top donors in ceremonial events or even governance roles: large donors might be invited to join a university’s foundation board or a state higher-education commission (in an advisory capacity). These recognition incentives leverage donors’ interest in leaving a legacy. They are codified not so much in explicit statutory language as in program guidelines and state-sanctioned university practices. By ensuring public acknowledgment – press releases, legislative commendations, naming ceremonies – states make it more attractive for individuals and corporations to contribute, as they receive reputational benefits alongside the satisfaction of advancing education.

In combination, these mechanisms (financial matching, partnership benefits, and public recognition) align the interests of private donors with public policy goals. The matching dollars provide the immediate financial reward, partnership access offers strategic business/research value, and recognition satisfies philanthropic and public-relations motives. States calibrate these incentives carefully – for example, setting minimum gift thresholds for matches (often $50,000 or $100,000 minimum) to ensure administrative efficiency and significant impact. The overall effect is to lower the “effective cost” of a donation (through matches or credits) and to amplify the returns (through prestige and collaboration), thereby motivating more frequent and larger gifts toward endowed faculty positions.

Successful Models and Case Studies

Several state programs stand out as successful models, providing case studies in how legislative incentives can boost endowed chairs and professorships:

Florida – Eminent Scholars and Major Gifts Program: Florida was an early pioneer with its 1985 law establishing the Trust Fund for University Major Gifts and Eminent Scholars Chairs. Under this program, private donations to state university endowments were matched by the state on a sliding scale – originally a 100% match for gifts over $2 million, with smaller gifts matched at 50–80%. This incentivized many large gifts. The University of Florida’s campaign in the late 1990s, for example, raised over $700 million, with $149 million coming from state matching funds. The program enabled Florida universities to establish hundreds of new endowed chairs and professorships.

Impact: Florida’s model dramatically increased philanthropic support for its universities; however, it also revealed challenges. During economic downturns, the state accumulated a backlog of owed matching funds (over $120 million by 2003), leading to delays that frustrated some donors. In one instance, a donor withdrew a $750,000 gift to a university due to the state’s delay in providing the promised match.

Lesson: A generous matching program can yield big gains in endowments and faculty excellence, but it requires consistent funding to maintain donor confidence.

Texas – Governor’s University Research Initiative (GURI) and TRIP: Texas has two major incentive programs. GURI, enacted in 2015, is a matching grant program focused on recruiting “distinguished researchers” (e.g., Nobel laureates or National Academy members) to Texas universities. The state offers up to $5 million in matching funds per hire to reimburse expenses for attracting these top faculty. This initiative, funded through the Governor’s office, has successfully lured high-profile scientists to Texas institutions by supplementing the endowed packages offered to them. Meanwhile, the Texas Research Incentive Program (TRIP) (created 2009) provides matches for research-focused endowment gifts at emerging research universities. TRIP’s tiered matching (50%, 75%, 100% as noted above) has proven effective – studies indicate TRIP was associated with significant increases in private gift revenue and even in additional grant funding for those universities.

Impact: Through TRIP, Texas leveraged private donations to help several second-tier universities (such as UT San Antonio, Texas Tech, University of Houston) progress toward “Tier One” research status. GURI has already facilitated the hiring of world-class scholars in science and engineering fields, boosting Texas’s research profile.

Lesson: Texas demonstrates a two-pronged approach – one program to build endowments broadly (TRIP) and another to target elite talent (GURI) – showing how state incentives can be tailored to different goals.

Kentucky – “Bucks for Brains” Research Challenge Trust Fund: Kentucky’s General Assembly launched this program in 1997 to strengthen research at its universities. The state provided $350 million over multiple bienniain funds that universities had to match dollar-for-dollar with private donations. The flagship University of Kentucky (UK) and University of Louisville received the bulk of these funds to endow chairs and research programs (two-thirds to UK, one-third to UofL), while a portion was allocated to a Regional University Excellence Trust Fund for smaller institutions to create “Programs of Distinction”.

Impact: The investment paid off handsomely. UK’s first campaign after the program’s launch blew past its $600 million goal, reaching $618 million in 2004 (with state matches contributing to that success). By the mid-2000s, over 400 new endowed professorships, chairs, and fellowships had been created at UK alone. The six regional universities also benefited, developing new faculty positions and programs (e.g. Eastern Kentucky University added five faculty posts in a justice and safety program of distinction). Kentucky’s universities credit “Bucks for Brains” with enabling them to recruit top researchers and to spur local economic development through innovation.

Lesson: A well-funded matching program can transform a state’s research landscape, especially if funds are strategically divided between major research universities and regional campuses.

North Carolina – Distinguished Professors Endowment Trust Fund: North Carolina’s legislature established this trust fund in 1985 to encourage private giving for endowed professorships across the UNC system. The state provides challenge grants that effectively match private gifts at different rates depending on the campus: the flagship and larger universities historically received $1 of state funds for each $2 of private funds (i.e., state covers one-third), whereas smaller institutions (HBCUs and special-focus universities) received a 1:1 full match. The program sets four levels of endowed chairs (from $500,000 up to $2 million total endowment) with corresponding match requirements.

Impact: This long-running program has resulted in hundreds of endowed chairs being established in North Carolina. By 2012, for example, there were dozens of new distinguished professorships across UNC campuses awaiting state match in a queue (demonstrating strong donor interest). The state did adjust the program over time – in 2023, it began to require new matched professorships to be in STEM fields to align with workforce needs. Despite occasional queues for funding, the program is credited with strengthening faculty excellence system-wide, especially by helping smaller campuses attract renowned professors they otherwise could not afford.

Lesson: North Carolina’s model highlights the importance of tailoring match ratios to institutional needs (greater incentives for smaller schools) and maintaining state support over the long term to fulfill matching pledges.

Georgia – Georgia Research Alliance (GRA) Eminent Scholars: Rather than a traditional matching endowment law, Georgia uses the non-profit Georgia Research Alliance (backed by state funds) to foster endowed chairs. Since 1990, GRA has partnered with research universities to create Eminent Scholar positions in areas strategic for state economic growth. The state invests $750,000 per chair through GRA, matched by $750,000 from private sourcesto endow a $1.5 million chair. These Eminent Scholars are typically star researchers recruited from elsewhere.

Impact: Georgia now has over 70 GRA Eminent Scholars in fields like biotechnology, engineering, and agriculture. They have been a magnet for research funding – accounting for $1 of every $4 in Georgia’s academic R&D funding in recent years. The program’s ROI for the state includes billions in federal and private research grants attracted by these scholars, as well as the spawning of startup companies and jobs.

Lesson: Georgia’s case shows that public-private funding of chairs can be woven into a broader economic development strategy. A state-chartered organization like GRA can provide flexibility in managing the matching process and recruiting talent while ensuring accountability for results.

Louisiana – Board of Regents Support Fund (Endowed Chairs and Professorships): Louisiana established an enduring model by using a windfall legal settlement in 1986 to seed an endowment for higher education. From this, the Endowed Chairs for Eminent Scholars Program (1986) and Endowed Professorships Program (1990) were created. Universities must raise 60% of an endowed chair ($600,000) and the state, via the Board of Regents, matches 40% ($400,000) to create a $1 million chair. (An institution can also create $2 million chairs with a $1.2M private / $800k state combination.) For the professorships, a smaller scale applies: $60,000 private with $40,000 state match for $100k professorships. To help smaller colleges, Louisiana even allows a temporarily inverted match(e.g. 40% private / 60% state) for the first few chairs at less wealthy campuses.

Impact: The growth has been dramatic – in 1985, Louisiana’s public campuses had under 100 endowed chairs & professorships total; by 2003 they had nearly 1,700, with about 1,600 of those created via the matching programs. The program leveraged $203 million in private donations, matched by the state, to build these endowments. LSU’s endowment alone grew from $79M in 1994 to $417M in 2003, largely thanks to matched gifts. Qualitatively, the influx of endowed positions helped Louisiana attract and retain top faculty and “made a positive difference” in academic excellence, cultural life, and economic development statewide.

Lesson: Louisiana’s approach underscores the value of a permanent funding source (an endowment) to sustain matches, and the importance of flexibility to include private institutions and smaller colleges in the benefits. Even relatively small matches (40%) can stimulate a huge increase in philanthropic giving if the program is consistent and well-publicized.

Maryland – E-Nnovation Initiative: A more recent example (launched in 2014), Maryland’s E-Nnovation Initiative Fund marries state economic development goals with university fundraising. The program, authorized by legislation, provides $8.5 million annually in state matching funds for research endowments at Maryland universities. To qualify, an institution must secure private donations for a chaired professorship in an approved scientific or technical field; the state then matches those funds to double the endowment. An oversight authority evaluates proposals to ensure they align with key industries.

Impact: In its first several years, the E-Nnovation program has spurred the creation of dozens of endowed chairs in areas like cybersecurity, neuroscience, and aerospace. By targeting matches to STEM fields, Maryland is intentionally building research capacity in sectors that promise high economic returns. Early reports show robust participation from both large research universities (Johns Hopkins, University of Maryland) and smaller colleges, with millions in private gifts being matched.

Lesson: Even with a modest annual budget, a focused matching program can quickly generate new endowed professorships in priority fields. Tying the program to the state commerce department (rather than the higher-ed agency) also signals the legislature’s view of endowed chairs as an economic investment, not just an educational expense.

Other states have implemented similar initiatives – South Carolina’s SmartState program (funded by $30 million per year from lottery funds) has created over 70 endowed chairs in areas like biomedicine and energy, and Oklahoma’s endowed chairs fund (begun in 1988) was so popular that it generated a backlog of unmatched pledges over $300 million in recent years. Wyoming and North Dakota, buoyed by energy revenues, launched challenge grant programs in the 2000s that offered to “double” any endowment gift (100% match) for their state universities. The common thread in these case studies is clear: when states put skin in the game, donors respond enthusiastically. Successful programs set transparent rules, align with state priorities (be it STEM research or regional development), and secure sufficient funding to honor the promised matches. The result, as seen in Texas, Kentucky, Louisiana, and others, is a significant expansion in the number of endowed faculty positions – which, in turn, elevates the academic and innovative capacity of those states’ public universities.

Impact on Stakeholders: Universities, Donors, and the Public

Legislative incentive programs for endowed chairs create a network of benefits and responsibilities affecting multiple stakeholders:

Impact on Public Universities: Universities are the primary beneficiaries, as these programs directly bolster their faculty and funding. With state matches, public institutions can recruit top-tier faculty whom they might not afford otherwise. Endowed chairs come with dedicated funding for salary, research, and labs, making offers to star professors more competitive. For example, the University of Kentucky credited the Bucks for Brains program for attracting researchers that helped it surpass fundraising goals and create 400+ new endowed positions. Similarly, Louisiana’s campuses saw an explosion in endowed professorships (from <100 to ~1,700) which “helped to retain… the state’s most accomplished faculty and aided in recruitment of other high-performing professors.”. Beyond individual hires, universities use these programs to build whole programs and research centers around eminent faculty. Endowed faculty often serve as anchors for new academic departments or interdisciplinary institutes. The influx of talent can raise an institution’s research profile (more publications, grants, and patents) and improve student experiences (through mentorship by distinguished scholars). However, with the influx of funds comes accountability: universities must follow rules on eligible uses (ensuring endowments support academic purposes as required) and often must report on how matching funds are used. Many laws require annual reports or certification that private gifts meet program criteria. Universities have responded by strengthening their advancement operations – more fundraising staff and better donor stewardship – to capitalize on these matches. In sum, these incentives empower public universities to grow and excel, but also push them to be more proactive and transparent in managing endowment gifts.

Return on Investment for Donors: From the donor perspective, state incentives fundamentally improve the ROI of giving to a public university. Philanthropists are keenly aware that “our money can go further and have a greater impact” when matched by public funds. A $1 million donation that is matched 1:1 effectively becomes a $2 million endowment, doubling the lasting support for the academic cause the donor cares about. Corporations likewise see financial leverage if a research gift is matched – essentially, they can double their investment in talent or innovation. Some states, as noted, sweeten the deal with tax benefits (offsetting part of the donation with a tax credit) which can reduce the net cost of the gift to the donor. Beyond monetary ROI, donors receive intangible returns. Chief among these is recognition – having an endowed chair named in honor of the donor or their designee is a prestigious legacy. Donors often join ceremonies installing the professor in the named chair, garnering positive publicity. Corporate donors may gain reputational capital as patrons of education and innovation, which can be leveraged in marketing or in recruiting skilled graduates. In some programs, donors also enjoy a relationship ROI: by endowing a chair, they form a lasting partnership with the university. Companies might collaborate with the lab of the endowed professor, and individual donors might be invited to special campus events or strategic boards. For example, universities in Georgia frequently involve the corporate sponsors of GRA Eminent Scholars in research review panels and networking events with faculty. All these benefits incentivize donors to give – and to keep giving. It’s worth noting that donors also expect accountability: they want assurance that the state will follow through on matches (hence the backlash in places like Oklahoma and Florida when matches were delayed) and that the endowment will be managed prudently. Successful programs maintain trust by being transparent about funding status and honoring commitments, which in turn keeps donors engaged for future gifts.

Public Accountability and Transparency: Since these initiatives involve public funds, strong accountability measures are typically built in. Legislatures and oversight bodies impose reporting requirements to track the use of state funds and the outcomes achieved. For instance, North Carolina’s Board of Governors must approve plans for each distinguished professorship before releasing state matching funds, ensuring the position aligns with institutional and state priorities. States like Connecticut and Massachusettsrequired annual reports from each institution on the amount of private donations raised and matched. Louisiana convened review panels to assess its Endowed Professorships Program and documented broad benefits (faculty productivity, economic contributions) to justify its continuation. Many states set sunset clauses or funding caps in the original legislation (e.g., Rhode Island’s 2000 matching program would end once $5M in state matches to URI had been reached or by 2003) so that lawmakers could revisit and evaluate the program’s performance. Another aspect of accountability is fiscal safeguards: some laws stipulate that endowment matches should not replace normal appropriations (to avoid the legislature simply swapping out general funding for matched funds). Public audits or legislative hearings are sometimes conducted, especially if problems arise (as seen when Oklahoma’s large backlog led to policy debates on funding bonds to cover the commitments). Overall, these measures protect the public interest by making sure that incentive programs truly add resources to higher education (not just substitute for existing funding) and that they deliver promised results in faculty excellence and economic impact.

Broader Public Benefits: The ultimate stakeholders are the citizens and communities who benefit from a stronger public university system. Endowed chairs enabled by these programs often lead to enhanced educational opportunities for students (who can learn from renowned professors and may access new scholarships or research projects funded by endowments). The research breakthroughs and innovation driven by endowed faculty can spur economic growth, new companies, and jobs – a clear win for the public. For example, Georgia’s eminent scholars have attracted billions in research grants and helped launch over 150 startup companies in the state. In South Carolina, the SmartState endowed chairs conduct research in areas like cancer treatments and advanced materials, directly addressing societal needs and creating high-tech industry clusters in the state. Even culturally, endowed positions in fields like humanities or public service can enrich the community through public lectures, policy research, or improved educational outcomes (e.g., an endowed education professor might train better teachers for the K-12 system). The public also benefits from the philanthropic culture these policies foster. By publicly celebrating donors and successful matches, states help cultivate a norm of giving to public institutions, which can have long-term benefits beyond the program’s scope. There is a transparency trade-off: the public expects results if their tax dollars are used as match. Thus, most programs ensure that if an endowed chair is created with state funds, it must be filled by a qualified scholar and maintained – no sitting on unfilled chairs or misusing endowment payouts. Some states even claw back funds if positions aren’t filled in a reasonable time or if matching funds aren’t raised as promised. When designed and executed well, these legislative initiatives create a virtuous cycle benefiting all stakeholders: universities rise in quality, donors see their visions fulfilled, and the public enjoys the educational, economic, and social returns on these investments.

Comparative Analysis Across States

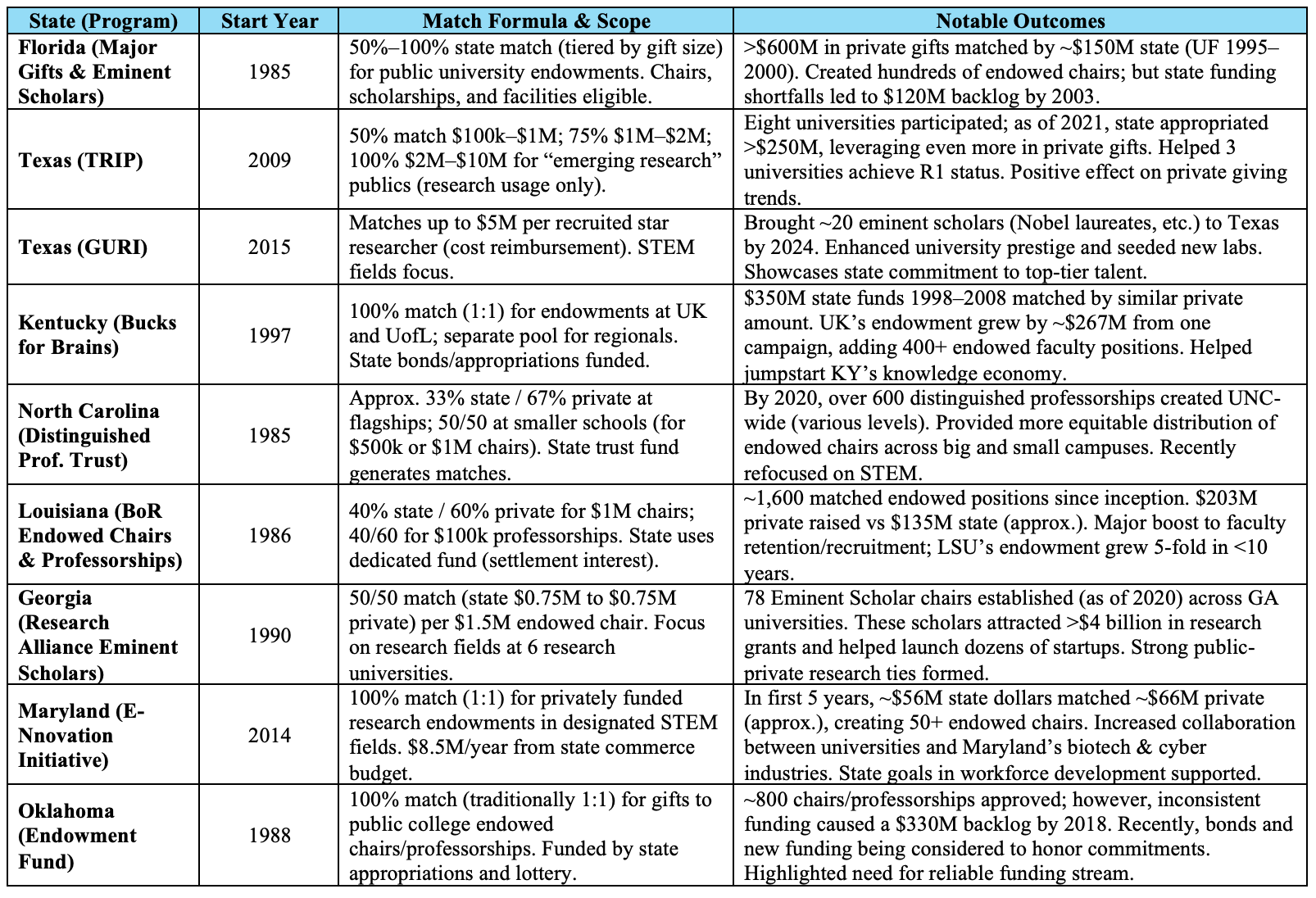

The landscape of endowed chair incentive programs reveals significant variation in structure and outcomes across different states. Below is a comparative overview, highlighting differences in program design, eligibility, funding levels, and effectiveness:

Structural Variations: Some state programs are permanent, ongoing funds (often with no fixed end date), while others are time-limited initiatives. For example, Tennessee’s Chairs of Excellence Trust (created 1984) is a permanent endowment managed by the state treasury, continuously available to match new endowed chair gifts. In contrast, Massachusetts’ original incentive program was intended to run only until a certain date or until a cap was reached (it was later extended by amendments). Similarly, Rhode Island’s 2000 program set specific end dates or funding caps for each public college. States with perennial programs (like North Carolina, Louisiana, Oklahoma) have the advantage of continuity – universities can plan long-term and cultivate donors over years – but they must weather economic cycles. States with one-off or episodic programs can make a big impact in bursts (Kentucky’s multi-year infusions, or Wyoming’s one-time matching appropriation) but risk losing momentum when the program pauses. The trend in recent years leans toward creating revolving or endowed state funds (to generate matching money from investment earnings) as seen in Louisiana and Kansas, as this is more sustainable than relying solely on annual budget appropriations.

Funding Sources and Levels: How states fund these incentives varies with their fiscal capacity and political will. General revenue appropriations are common – e.g., Maryland dedicates $8.5M each year from its budget, and Texas allocates funds to TRIP and GURI through its budget process. Some states tapped special funds: lotteries (South Carolina’s $30M/year from the Education Lottery), tobacco settlement or oil revenue (Louisiana’s $540M legal settlement principal, North Dakota’s oil-tax–funded Higher Ed Challenge Fund). The magnitude of state investment ranges widely. On the higher end, Oklahoma’s legislature had authorized over $300M (in bonds, albeit vetoed) to clear its endowed chair matching backlog, and Kentucky put $350M into Bucks for Brains over about a decade. On the lower end, states like Maine or Nevada have offered much smaller matching grant pilot programs (or none at all), due to limited budgets. Importantly, the matching ratio often correlates with state wealth and priorities: wealthy states or those aiming to become research powerhouses tend to offer richer matches (e.g., Texas’s 100% match for large gifts, Florida’s 100% for $2M+ gifts), whereas states with tighter finances might stick to 50% matches or require a larger private share. Tax incentives, where used, also reflect differences: a high-tax state can offer credits to offset some tax burden (at cost to the state), while no-income-tax states (like Florida or Texas) cannot use that tool and instead rely on direct grants. The variety in funding approaches shows there is no one-size-fits-all solution; each state calibrates to its economic reality. Yet, across the board, every public dollar tends to bring in multiple private dollars – a leveraging effect universally valued.

Eligibility and Scope: States differ on which institutions and disciplines are eligible for matches. Most programs target public universities exclusively, as the goal is to strengthen public higher education. However, a few states extended incentives to private colleges as well, typically when the program’s aim is broad economic development or when using a general higher-ed endowment fund. Louisiana’s Board of Regents programs, for instance, guarantee a few matches per year to private institutions in the state, under the logic that any research activity benefits Louisiana. Another example is New Mexico’s endowment fund (created in 2022), which allocates matching funds to both public and tribal colleges for endowed faculty positions (though not to private colleges). In contrast, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and similar programs explicitly limited matches to the state university systems, state colleges, and community colleges. Within public systems, states may prioritize certain campuses: e.g., Texas TRIP defines a set of eight “emerging research universities” eligible for its matches (excluding the already well-funded flagships). North Carolina’s program stratified schools into tiers (Research I universities vs. “focused growth” smaller campuses) with different match levels. Regarding disciplines, the early programs were generally open to all fields – endowed chairs in humanities or liberal arts were as eligible as those in engineering. But there is a recent trend of targeting STEM and high-demand fields. In 2023 North Carolina restricted new matches to STEM areas, and Maryland’s program from the start focuses on scientific/technical research chairs. This targeting aligns the incentive with workforce and innovation policy, but some states still value supporting a broad spectrum of academic excellence (for example, Florida’s Major Gifts Trust Fund explicitly included library endowments and scholarships alongside chairs). The scope of what counts as an “endowed professorship” can also vary – many states allow splitting a large match into several smaller “endowed professorships” (especially at teaching-focused schools where a $100k endowment for a professorship may be the goal). Ultimately, states design eligibility rules to distribute funds in line with their policy objectives, whether that’s bolstering flagship research capacity, uplifting regional colleges, or seeding growth in certain industries.

Outcomes and Effectiveness: Comparing outcomes, states that sustained their programs over many years have seen the most dramatic growth in endowed faculty positions. Louisiana and North Carolina, with continuous programs since the 1980s, each now boast well over a thousand matched endowed positions, infusing their universities with talent. Kentucky and Georgia, with large state investments, saw major jumps in research stature (UK and UofL moved up in research rankings, and Georgia’s universities became leaders in tech-driven research). Texas in a short time funneled hundreds of millions into its emerging research universities via TRIP, contributing to three institutions reaching Carnegie R1 (top research) status by 2022. Massachusetts’ program, though stop-and-go, still leveraged $100M private for $50M state in a decade, helping UMass campuses expand their endowments significantly. On the flip side, states that never implemented a match program or halted funding show a gap. For instance, California – which has no statewide matching fund for university endowments – relies purely on university-led fundraising; while UC and CSU have grown endowments, some observers note California “left money on the table” by not offering matches during the boom philanthropic years (and indeed UC launched its own internal match initiatives to compensate). States like Illinois or New Jersey that lack such programs have seen more modest growth in public university endowments, often trailing their counterparts in matched-fund states of similar size (this is anecdotal but supported by CASE surveys of advancement officers). However, correlation isn’t strict causation – factors like alumni wealth, institutional fundraising capacity, and baseline state funding also play roles. One clear pattern is that legislative design choices impact donor behavior: overly complex rules or uncertain funding can dampen enthusiasm. Oklahoma’s experience (where donors kept giving but then had to wait years for matches) somewhat hurt donor trust. In contrast, Michigan’s recent smaller-scale match program for community college endowments (started 2020) kept things very simple (1:1 match up to a modest cap) and saw all eligible colleges meet the challenge quickly, suggesting even small incentives work if well-designed. Efficiency is another comparative metric – some states get a bigger bang per buck. For example, Connecticut’s program by 2014 had the state put in about $177 million which yielded over $471 million in donations just at UConn (roughly $2.66 raised per $1 state). Kentucky got about $700M private for $350M state (a 2:1 leverage). Florida at one point had an even higher leverage due to tiered matches. These differences often trace back to match ratio and donor base. Accountability measures also affect outcomes: states that built in careful oversight generally avoided scandals or misuse of funds; there have been virtually no cases of matched endowment funds being misappropriated, which speaks to strong governance frameworks (e.g., requiring funds to be placed in regulated endowment accounts and used only for the intended chair or scholarship).

To illustrate some key differences, below is a comparison table of selected state programs:

This comparative snapshot illustrates the diversity: some states like Florida and Texas aimed to maximize private input with tiered matches, others like North Carolina and Kansas focused on equity and coverage (ensuring all campuses benefit). The results generally affirm that higher match ratios and stable funding yield greater growth in endowments. However, even smaller programs can make a difference, especially for institutions that previously had little culture of philanthropy – in those cases, a state match can be the spark that gets donors (including alumni and local industries) engaged for the first time.

In correlating legislative design with growth in endowed positions, a few patterns emerge:

States that invest early and consistently (North Carolina, Louisiana) accumulate a large number of endowed chairs over decades, fundamentally changing their academic landscape.

Programs that target research universities (Texas, Georgia) show gains in research output and rankings, whereas those inclusive of teaching-focused colleges (Massachusetts, Kansas) spread benefits across the system, sometimes at the cost of concentrating excellence. Both strategies have merit depending on state goals.

Generosity of match drives donor behavior: Florida’s and Texas’s willingness to fully match big gifts led to a spate of multimillion-dollar donations in those states. In states with lower matches or caps, donors may still give but could be less incentivized to stretch into higher gift brackets.

Economic alignment (focusing on STEM, requiring industry partnership) can maximize public benefit, but if too restrictive, might leave available donor money on the table (for instance, a donor who wants to endow an arts professorship might be discouraged if only STEM gifts qualify). States must balance strategic focus with flexibility to attract all kinds of philanthropy.

Finally, one clear lesson across the comparative analysis is the importance of legislative commitment and adaptability. The most successful states treated these incentive programs not as one-off experiments but as evolving policy tools – adjusting match ratios, extending programs, or refilling funding as needed (Massachusetts revisited its program to add funds in 2019; North Dakota re-launched challenge grants multiple times when oil revenues allowed). Endowing a professorship is a long-term proposition, and states that mirror that long-term outlook in their policy design tend to reap the greatest rewards in academic excellence and economic impact.

References:

1. Council for Advancement and Support of Education (2004). Select Government Matching Fund Programs: An Examination of Characteristics and Effectiveness. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497601.pdf

2. Hildreth Institute. (n.d.). Testimony: An Act Relative to the Endowment Match Program. https://www.hildrethinstitute.org/blog/testimony-an-act-relative-to-the-endowment-match-program

3. University of Texas at San Antonio. (n.d.). Texas Research Incentive Program (TRIP). https://www.utsa.edu/giving/how-to-give/TRIP.html

4. Strike Tax Advisory. (n.d.). Arkansas R&D Tax Credits. https://www.striketax.com/state-rd-credits/arkansas-r-d-tax-credits

5. Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration. (2022). Instructions for AR1000TC: Schedule of Tax Credits and Business Incentive Credits. https://www.dfa.arkansas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022_AR1000TC_Schedule_of_TaxCredits_andBusiness_IncentiveCredits_Instructions.pdf

6. Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts. (2022). University System of Georgia: Matching funds for endowed chairs and professorships (Report No. 22-06). https://www.audits.ga.gov/ReportSearch/download/15627

7. South Carolina Legislature. (n.d.). South Carolina Code of Laws § 2-75-30 – Research Centers of Economic Excellence Act. Justia. https://law.justia.com/codes/south-carolina/title-2/chapter-75/section-2-75-30/

8. University of Kansas. (n.d.). Kansas Partnership for Faculty of Distinction Program. https://services.ku.edu/TDClient/818/Portal/KB/ArticleDet?ID=21173

9. Office of the Texas Governor. (n.d.). Governor’s University Research Initiative (GURI). https://gov.texas.gov/business/page/guri

10. University of Louisville. (n.d.). About Bucks for Brains. https://louisville.edu/bucks-for-brains/about

11. University of North Carolina System. (2003). Distinguished Professors Endowment Trust Fund: UNC policy manual, section 600.2.3.1[G]. https://www.northcarolina.edu/apps/policy/doc.php?id=2823

12. UNC General Alumni Association. (2023, March 8). Trustees, administrators assure continued funding of humanities. https://alumni.unc.edu/news/trustees-administrators-assure-continued-funding-of-humanities/

13. Georgia Research Alliance. (2021, October 14). Georgia Research Alliance: National model for university–industry partnerships. https://gra.org/stories/1046/

14. Maryland Department of Commerce. (n.d.). Maryland E-Nnovation Initiative Fund (MEIF). https://commerce.maryland.gov/fund/maryland-e-nnovation-initiative-fund-(meif)

15. South Carolina Commission on Higher Education. (2023). 2022–2023 SmartState Program annual report and audit. https://www.scstatehouse.gov/reports/CommissiononHigherEd/2022-2023%20SmartState%20Program%20Annual%20Report%20and%20Audit.pdf

16. Collins, R. (2023, November 2). Colleges seek more state borrowing for professors. Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs. https://ocpathink.org/post/independent-journalism/colleges-seek-more-state-borrowing-for-professors

17. University of Wyoming Foundation. (2024). Legislative report 2024.https://www.uwyo.edu/foundation/publications/legislative-report/legislativereport2024.pdf

18. Western Kentucky University. (n.d.). Bucks for Brains. https://www.wku.edu/bucks/

19. University of Massachusetts Amherst. (2023, August 3). State legislature approves higher ed endowment match program. https://www.umass.edu/news/article/state-legislature-approves-higher-ed